Rubber was already known to the Maya, who used it to produce waterproof containers and elastic balls and to bond shoes. It is obtained by tapping the rubber tree, which releases a liquid known as latex or milky sap. This liquid is collected in containers and further processed. Latex contains 25 to 35% rubber. The English term rubber originates from its early use for rubbing out pencil marks. By contrast, in many languages, natural rubber is also known as caoutchouc, a term derived from the indigenous words “cao” for tree and “ouche” for tear, meaning “the weeping tree.”

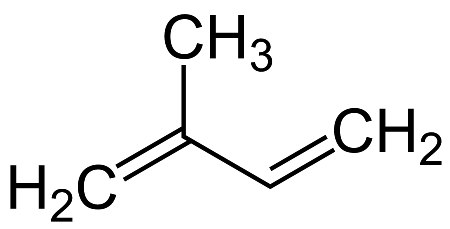

A rubber molecule consists of 3,000 to 10,000 isoprene units. The chemically correct name for isoprene is 2-methylbuta-1,3-diene; its structural formula is shown in the following figure.

The material is soft and highly elastic; at 0 °C it becomes hard, and above +150 °C it becomes sticky and flows. It is soluble in gasoline, chlorinated hydrocarbons, and oils. Due to the double bonds contained in the isoprene units, it is reactive and is attacked by atmospheric oxygen and UV radiation.

Originally, rubber referred only to natural rubber. Today, the term also includes synthetic polymers that can similarly be vulcanized from a plastic to a rubber-elastic state. In technical applications, the vulcanizates of natural and synthetic rubbers are referred to as rubber or elastomers.

Rubber – A Rubber-Elastic Plastic

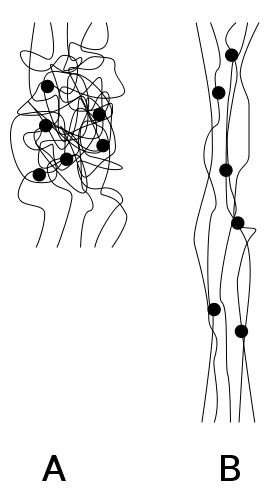

According to German standard DIN 53 501, “rubber is an uncrosslinked but crosslinkable polymer with rubber-elastic properties”[1]. Rubber-elastic means that a piece of the material returns to its original shape after being deformed—such as by twisting, pulling, or bending—and then released.

These tangles allow a high degree of mobility of the loosely crosslinked polymer chains. Under mechanical stress, the polymer chains are stretched and the material as a whole elongates. When the load is removed, the polymer chains coil up again and the material contracts.

In the manufacture of elastomers, rubbers are mixed with various substances, shaped into the desired form, and then vulcanized. Such rubber compounds consist of several rubbers or blends of rubbers and other plastics, as well as additives such as plasticizers, fillers, processing aids, and anti-aging agents.

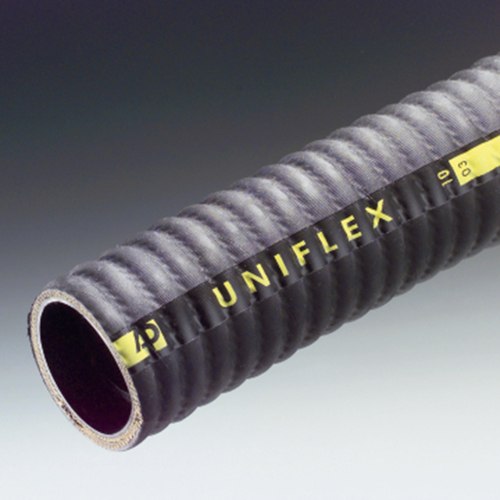

Vulcanization can be carried out with sulfur, peroxides, or infrared radiation. Materials with a low degree of crosslinking are referred to as soft rubber, while those with a high degree of crosslinking are called hard rubber. A very high degree of vulcanization leads to thermosets. Rubber-elastic elastomers are now used in the manufacture of rubber hoses, seals, and semi-finished products such as rubber sheets and rubber mats.

Rubber Groups: Natural Rubber vs. Synthetic Rubber

A distinction is made between natural rubber, abbreviated NR from the English “natural rubber,” and synthetic rubber, abbreviated SR from the English “synthetic rubber,” i.e. synthetically produced elastomers.

Synthetic rubber is produced by polymerization of monomers. Polymerization of identical monomers yields a homopolymer. If two different monomers are polymerized, the product is referred to as a copolymer; polymerization of three different monomers results in a terpolymer.

The German standard DIN ISO 1629 regulates the international abbreviated designations of the various synthetic rubber types based on the chemical structure of the main chain. According to this system, each rubber is assigned a short designation consisting of two to five letters. The final letter characterizes the chemical composition of the polymer chain and serves as the group identifier. The preceding letters indicate the monomer or monomers from which it is composed.

Rubbers are divided into eight different groups: those with a saturated polymer chain belong to group M, those with an unsaturated polymer chain to group R. If the main chain contains nitrogen atoms, the rubber is assigned to group N; if oxygen is present, to group O; if sulfur is present, to group T. If phosphorus and nitrogen are present in the main chain, it belongs to group Z; if carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen are present, to group U. Group Q stands for siloxane groups in the polymer chain.

In rubber abbreviations, the initial letters may indicate the presence of certain atoms or functional groups in the side chain, such as C for chlorinated, B for brominated, or X for carboxylated. Rubbers of groups R and M account for the largest share of processed elastomers.

Rubbers of Group R

Group R rubbers with double bonds in the main chain are produced by polymerization of at least one diene. A diene is a hydrocarbon compound with two double bonds.

In the case of 1,3-butadiene, these are conjugated, meaning that the two double bonds are separated by a single bond. One double bond participates in the polymerization to extend the chain, while the other remains in the side chain. Crosslinking can occur via the main chain or the side chain. Important rubbers belonging to group R include natural rubber (NR), butadiene rubber (BR), chloroprene rubber (CR), isoprene rubber (IR), acrylonitrile-butadiene rubber (NBR), styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR), and isobutylene-isoprene rubber (IIR, butyl rubber).

Rubbers of Group M

Rubbers of group M, derived from “methylene,” are also referred to as olefin rubbers. Since the main chain contains no double bonds, crosslinking cannot occur at the main chain but proceeds via the side chain. Of greatest economic importance is ethylene-propylene-diene rubber (EPDM), a terpolymer of ethylene, propylene, and a diene. Other representatives of group M include polychlorotrifluoroethylene–vinylidene fluoride copolymer, abbreviated CFM and better known as fluoroelastomer, ethylene-propylene copolymer (EPM), chlorosulfonated polyethylene (CSM), ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer (EVM), and rubbers with fluorine or fluoroalkoxy groups on the polymer chain (FPM).

General-Purpose Rubbers and Specialty Rubbers

According to W. Baumann[1], rubbers are classified by market share into universally usable rubbers, known as general-purpose rubbers, specialty rubbers, and specialties. In 1998, general-purpose rubbers accounted for approximately 64% of the Western European market. These include NR, SBR, BR, and IR. Specialty rubbers, including EPDM, IIR, CR, and NBR, accounted for 33%, while specialties such as fluoro- and silicone rubbers, CSM, and EVM accounted for just under 3%.

Properties and Applications of General-Purpose Rubbers

SBR, marketed under the trade name Buna S®, has the largest share among general-purpose rubbers. It is inexpensive and exhibits better aging and heat resistance than natural rubber, but poorer elastic properties. Approximately 50% of total production is processed in the tire industry. Other applications include conveyor belts, soles, rollers, drive belts, as well as pharmaceutical, surgical, and sanitary products and food-contact articles.

BR, marketed under the trade name Buna N®, exhibits high elasticity, excellent abrasion resistance, and strength comparable to NR. Almost 90% of BR production is used in the tire sector. Due to its high abrasion resistance, it is also used in conveyor belts and shoe soles.

IR, the synthetic variant of natural rubber, shows very low gas permeability and high resistance to oxygen, but only limited resistance to oils and fats.

Properties and Applications of Specialty Rubbers

NBR, marketed under the trade name Perbunan®, is distinguished among all rubbers by the highest resistance to fuels, fats, and oils. It is used wherever this resistance is required in combination with good mechanical properties, good aging resistance at elevated temperatures, and good abrasion resistance. Main areas of application include oil- and fuel-resistant seals as well as mineral oil hoses and fuel hoses.

NBR also plays an important role in the manufacture of valves and fittings, diaphragms, clutch and brake linings, conveyor belts, safety footwear, foam rubber and cellular rubber, as well as in the food industry when processing fatty products.

Hydrogenation yields hydrogenated NBR, abbreviated HNBR, which has higher wear resistance and better ozone resistance than NBR. However, HNBR is significantly more expensive.

EPDM, available under the trade name Keltan®, is regarded as a sustainable material due to its durability. Owing to its saturated main chain, the polymer is resistant to temperature loads up to +120 °C and to oxidation. It also exhibits high resistance to weathering, aging, and ozone, as well as good chemical resistance. In the construction sector, it is used for sealing profiles for windows and façades, sealing membranes and sheets for roofs, water basins, and pond liners. Other applications include seals for drinking water and wastewater, EPDM hoses, cellular rubber and foam rubber, and insulation for low-voltage cables.

CR, better known as Neoprene®, exhibits better resistance to weathering, ozone, and heat than NR, NBR, and SBR, but lower resistance than HNBR or EPDM. Where good flame retardancy is required in addition to these properties, CR is used. This elastomer is employed for window and construction profiles, linings and cable sheathing, tires, drive belts, hoses and seals, as well as gloves for laboratory work. Neoprene suits for water sports are also well known.

IIR, marketed under the trade name Polysar Butyl®, is characterized by very low gas permeability, good damping properties, high electrical insulation, elastic behavior at very low temperatures, and good resistance to acids and alkalis. Applications include tires, inner tubes, seals, diaphragms, cable insulation, chemical protective gloves, and as a base for chewing gum. Where rubber-elastic, gas-tight hoses are required, butyl rubber hoses are the material of choice.

Properties and Applications of Rubber Specialties

Fluoroelastomers (FPM) are usually co- or terpolymers of vinylidene fluoride, hexafluoropropene, and tetrafluoroethylene. Trade names include Viton®, Fluorel®, or Tecnoflon®. They exhibit high resistance to temperature, chemicals, ozone, and weathering, flame retardancy, high abrasion resistance, and low gas permeability. They are used in specialized applications in automotive engineering, the aerospace industry, and oil production as seals and hoses, as well as protective gloves.

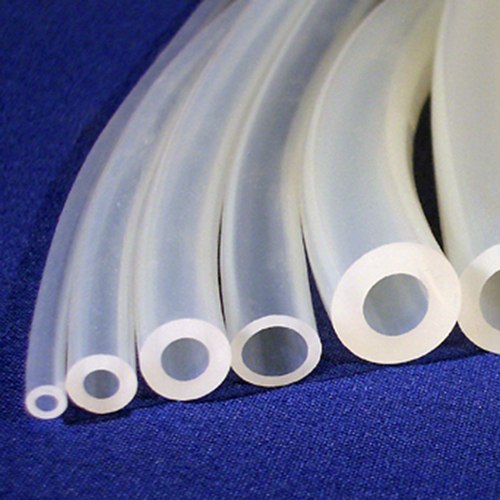

In silicone rubbers, unlike other elastomers, the polymer chain consists of alternating silicon and oxygen atoms. These rubbers are classified according to the side chains bonded to the silicon atoms. MQ have methyl side chains, VMQ vinyl-methyl groups, and FMQ fluoroalkyl groups. They can be used over a wide temperature range from −100 °C to +260 °C and exhibit almost temperature-independent flexibility and elasticity, outstanding resistance to weathering and UV radiation, long service life, and electrical insulation properties. In the construction sector, they are used as sealants for filling joints; in medical technology as silicone hoses, breathing bags, incubators, and for the production of molding and potting compounds.

However, from the wide variety of rubbers with different properties, a suitable material can likely be found for almost any application.

Text sources: [1]: W. Baumann et al., Kautschuk und Gummi, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 1998

Image sources: Featured image | © wasdok101 – stock.adobe.com Structural formula of isoprene | © Jü, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Milky sap of the rubber tree | © Paitoon – stock.adobe.com Schematic representation of an elastomer | Polymer_picture.PNG:Mdufalla at en.wikipediaLater versions were uploaded by Cb2292 at en.wikipedia.derivative work: CameronSS, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine