Many people are familiar with nylon and the related polymer Perlon as components of textiles. However, polyamides are also used in vehicles and under the hood. Fuels, for example, are frequently transported through PA hoses. But what other application possibilities exist? And what are the key advantages of these materials?

A synthetic polymer as a substitute for silk

It was the American chemist Wallace Hume Carothers (1896 1937) who, in 1935, succeeded for the first time in producing a synthetic fiber from a polyamide with nylon. Even earlier, he had been involved in the development of Neoprene®, a synthetic rubber that is not only used for thermally insulating sports textiles, but has also found its way into numerous technical applications in the form of cable sheathing, hoses, and sponge rubber seals.

Carothers also recognized the great potential of nylon, which can be spun directly from a low viscosity polymer solution into an elastic filament.

As early as 1938, the new plastic nylon was introduced to the US market by DuPont with a large scale advertising campaign under the slogan: “A better fiber for a better life.”

During the war years, nylon in the United States was reserved exclusively for military use. It was employed for parachutes, parachute cords, and flight suits, thus replacing silk, which had previously been sourced primarily from Japan.

Two related polymers: nylon and Perlon

Carothers produced his new plastic from the two components adipic acid and hexamethylenediamine. Adipic acid is a dicarboxylic acid (hexanedioic acid), while hexamethylenediamine is, as its name suggests, a diamine. The carboxyl group (–COOH) reacts with the amino group (–NH2) to form a peptide bond (–NH–CO–), which represents the basic structural unit of all polyamides.

Within the polymer, the two monomer components are arranged alternately, forming long polymer chains. Instead of the adipic acid and hexamethylenediamine used by Carothers, other monomers can also be employed. In 1938, the German chemist Paul Schlack (1897 1987) succeeded in producing Perlon, which is related to nylon, from ε caprolactam. When heated, the ring shaped ε caprolactam is converted into ω aminocaproic acid (chemically: ω aminohexanoic acid), which has a carboxyl group at one end and an amino group at the other. It is therefore described as bifunctional and can react, so to speak, “with itself” to form long chain polyamides.

Both plastics are thermoplastics and exhibit similar material properties. They can be drawn into long, elastic fibers, are tear resistant and lightweight, and differ mainly in their melting points, which depending on quality are around 220 °C for Perlon and approximately 260 °C for nylon.

Two polymers with very similar structures

The nomenclature of polyamides is defined in the international standard DIN ISO 1043 1. According to this standard, PA is the abbreviation for all polyamides, followed by the number of carbon atoms in the monomers. If a bifunctional monomer is used, as in the case of Perlon based on ω aminohexanoic acid with six carbon atoms, the abbreviation is PA 6. If, on the other hand, a dicarboxylic acid reacts with a diamine, as is the case with nylon, the carbon atoms of both monomers are counted and listed consecutively. Nylon therefore has the official designation PA 6.6. Occasionally, though not in accordance with the DIN standard, the dot is omitted and PA 66 is used instead. Less common is the replacement of the dot with a slash (PA 6/6).

In addition to nylon and Perlon, other polyamides such as PA 11 or PA 12, the lightest of the polyamide plastics, have also gained economic importance. PA 11 is based on ω aminoundecanoic acid with eleven carbon atoms, which is obtained from ricinoleic acid, the main component of castor oil derived from castor beans. PA 11, with the trivial name Nylon 11, is therefore regarded as a bioplastic. Its main area of application is the coating of pipelines, and it is marketed under the trade name Rilsan®.

The starting material for PA 12 is ω aminododecanoic acid, whose twelve carbon atoms give Nylon 12 its name. The properties of PA 12 are similar to those of PA 6 and PA 6.6; however, its melting point of less than 180 °C is significantly lower than that of all other commercially available polyamides.

PA 12 is used both for corrosion protective coatings on metals and for aroma tight food packaging. It is marketed under the trade name Grilamid®.

If one of the monomers contains an aromatic component, this is indicated by an additional abbreviation. For example, “T” stands for terephthalic acid, and PA TT refers to the poly(p phenylene terephthalamide) formed from the monomers terephthaloyl chloride and phenylenediamine. Its trivial name is Kevlar®, a particularly rigid, tear resistant, and temperature resistant plastic used in bulletproof vests, safety helmets, and aircraft components.

Fibers or granules

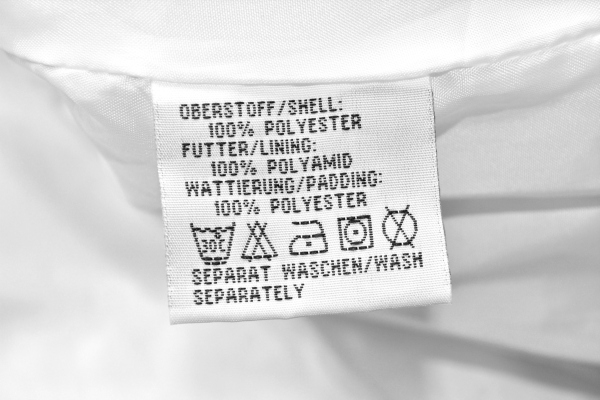

Nylon and Perlon remain the most widely used polyamides today. In 2015, seven million tonnes of polyamides were produced, with more than 50% processed into fibers and films. Both polymers are therefore found as fibers in all kinds of textiles, in ropes or sails, and in numerous everyday items, such as the bristles of toothbrushes.

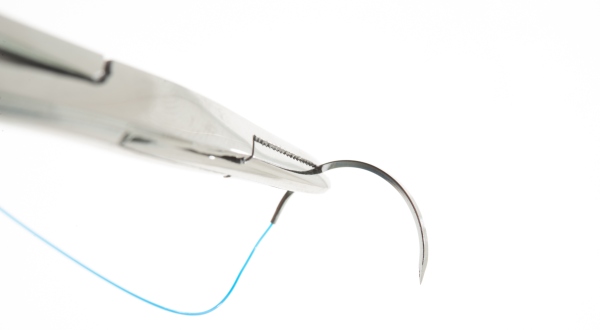

In surgery, monofilaments made of Perlon (PA 6) and nylon (PA 6.6) are used as non resorbable suture material due to their strength and physiological compatibility. Medical technology also uses polyamide hoses for in vitro cannulation.

Polyamides are not only produced in the form of fibers, but also as granules, which can be further processed into finished parts or semi finished products using typical thermoplastic methods such as injection molding, blow molding, or extrusion. Semi finished products such as plastic sheets or round bars can be mechanically processed by drilling, milling, or grinding. Individual components can also be permanently joined using joining techniques such as welding or bonding.

Properties that make polyamide unbeatable

Use in the automotive industry

Elasticity and tear resistance are key reasons for the versatile use of polyamides. Due to their strength and stiffness, as well as their resistance to organic solvents such as alcohols, acetone, benzene, and fuels, they are also of interest for other industrial sectors, particularly the automotive industry.

Fuel hoses made of polyamides are just as indispensable for vehicle construction today as many other polyamide components that replace metals such as aluminum or steel, enabling significant weight savings while maintaining comparable properties. Glass fiber reinforced plastics (GFRP) exhibit markedly different material characteristics compared to pure plastics. Polyamide glass fiber compounds, for example, offer higher stiffness and hardness as well as improved chemical and hydrolysis resistance compared to unfilled polyamides. In addition, one of the disadvantages of polyamides, their relatively high water absorption, can be significantly reduced by the addition of glass fibers.

Due to their high wear resistance and good sliding properties, polyamides are also used in the manufacture of plain bearings, drive belts, gears, or rollers. The addition of carbon fibers can further improve these sliding properties.

Important in electronics

The second largest consumer of polyamides is the electronics industry. Polyamides are particularly suitable for housings and for insulating electronic components, as they exhibit high electrical insulation strength and resistance to tracking. At the same time, polyamides can be selectively modified to be electrically conductive by incorporating metals or graphite, opening up further application possibilities in the electrical and electronics sectors.

Filtration applications of polyamides

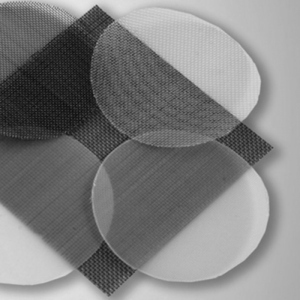

Finally, filtration units are equipped with nylon filters, such as sieve filter candles or woven meshes. These are used in laboratory and analytical technology, chemical process engineering, and other technical fields to separate solid particles from liquids or gases.

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine