Prostheses, implants and suture materials all have one requirement in common: they should cause as little adverse effect as possible on the surrounding tissue and on the human body as a whole. A term that is repeatedly used in connection with medical materials is “biocompatibility”. But how is biocompatibility defined, and to what extent does a USP Class VI classification provide information on how “biocompatible” a material actually is?

What is Biocompatibility?

Since the 1940s, scientists have been interested in how the body reacts to implanted substances. However, the term biocompatibility itself was probably not used until around 1970.

Biomaterials are non-living natural or synthetic materials that are used in contact with the living body and therefore must meet the primary requirement of being biocompatible. As there are a wide range of applications and exposure times for biomaterials in medical technology, biocompatibility is a context-dependent property and does not have a single, absolute definition. Instead, many different definitions exist. Over time, existing definitions have been adapted and expanded in line with new scientific findings.

For a long time, biocompatible materials were regarded as chemically and biologically inert within the human body. This view has since been revised, as a response from the body always occurs. The IUPAC defines materials as biocompatible if contact with a living system does not produce any adverse effect.[1] Another frequently cited definition is that of David F. Williams: “The ability of a material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application,” which can be roughly translated as: “Biocompatibility is the ability of a material, when used, to lead to an appropriate host response.”[2]

What exactly constitutes an “appropriate host response” is not defined in more detail and was presumably formulated deliberately in such an open manner.

Biocompatibility as a Material Property?

The term “biocompatibility” encompasses a whole range of material characteristics that must be fulfilled depending on the application. For this reason, biocompatibility is often regarded as a pure material property. However, the characteristics of the manufactured implant itself, such as its density, surface structure and mechanical properties, are also important criteria. In many cases, several materials are processed together, which means that interactions between different materials may also occur. For this reason, in biomedical technology it is essential to test not only the raw materials but also the finished product.

Today, the term “biocompatible material” is discussed controversially in medical research, and Williams himself addressed this issue in 2014 with his publication entitled “There is no such thing as a biocompatible material.”[3]

Any foreign substance introduced into the human body triggers a more or less pronounced immune response, known as a “foreign body reaction”. Biocompatible materials also trigger such a reaction, albeit to a comparatively lesser extent. For this reason, researching foreign body reactions in order to minimise them has become an important field of research today.[4]

As biomaterials can therefore never be completely inert and because biocompatibility is a very broad term, alternative classifications such as bioinert, biotolerant and bioactive have been introduced to allow for clearer differentiation.

How Can Biocompatibility Be Measured?

Even though, as explained above, the biocompatibility of a medical device depends on factors beyond the material itself, we will nevertheless continue to use this terminology for the sake of simplicity, even if it is not entirely accurate.

It is, of course, sensible to first test the raw materials of a medical product for biocompatibility in order to ensure that the finished product is also highly likely to be biocompatible. As a rule, the raw materials are tested by their manufacturer, while the finished product is tested by the medical device manufacturer itself.

In general, tests are carried out that fall into one of two categories. On the one hand, it is determined whether and to what extent (toxic) components can be released from a material. On the other hand, in vitro (outside the living organism) or in vivo (on the living organism) tests are performed to determine the immune response of the body to the biomaterials being tested.

USP Class VI Approval and Cytotoxicity Testing According to USP <87>

An important classification, particularly for medical plastics, is the USP Class VI rating, which is described in the United States Pharmacopeia, a handbook for pharmaceuticals that is reissued annually. Article <88> sets out guidelines and test protocols for medical elastomers and other plastics and polymeric materials.

USP Class VI is the strictest of the six categories and is regarded as a pharmaceutical approval for polymeric materials.

The biomaterials are subjected to in vivo tests in the following three areas: acute systemic toxicity, intracutaneous reactivity and a short-term implantation test. USP Class VI approval is often treated as a pharmaceutical approval for medical plastics; however, many authorities regard it only as a minimum requirement for use in medical products. More detailed information on USP Class VI certification can be found in our article: USP Class VI approval – What does it mean?

In addition to USP <88>, USP <87> also describes a test procedure used to assess the biocompatibility of biomedical plastics. This test examines the cytotoxicity of a material, i.e. the extent to which cells are damaged by the material. In this in vitro test procedure, extracts of the material are introduced into a cell culture medium and the inhibition of growth of mouse fibroblasts is observed. In practice, the cytotoxicity test is often critical, as in around 90 % of cases the material fails the test. For this reason, if this test is required, it often makes sense to carry it out first.

Comparison of Tests According to USP Guidelines and the DIN EN ISO 10993 Standard

Stricter approval requirements are defined by the DIN EN ISO 10993 guideline, which is becoming increasingly important. ISO 10993-1 lists the required tests, while the further ISO 10993 standards describe them in more detail.

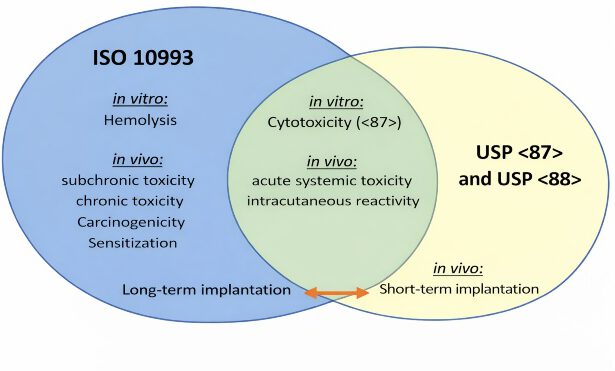

The following illustration provides a rough overview of both classifications:

Even though, as shown in the graphic, some tests overlap, the minimum requirements for a test often differ. If both USP Class VI and ISO 10993 certifications are required, the stricter requirements can be fulfilled, meaning that some tests can be omitted compared to two separate certifications.

A USP Class VI classification is less time-consuming and more cost-effective than testing for ISO 10993 compliance and nevertheless represents a good initial decision-making aid for medical device manufacturers when selecting suitable plastics.

Which biocompatibility test is required depends strongly on the respective application and therefore also on the duration of use of the finished product. ISO 10993 was developed for medical products that remain in the human body permanently or for very long periods of time; for shorter applications, a USP Class VI or even a lower Class certification is often sufficient.

In the European Union, approval of medical devices requires a conformity assessment procedure in accordance with the Medical Device Regulation (MDR), which generally includes a clinical evaluation.

At the same time, it should be kept in mind that, as explained at the beginning of the article, factors other than material properties also influence biocompatibility.

Sources: [1] Terminology for Biorelated Polymers and Applications, IUPAC Recommendations 20XX [2] The Williams Dictionary of Biomaterials, D. F. Williams, 1999, ISBN 0-85323-921-5 [3] D. F. Williams, Biomaterials 2014, 35, 10009–10014. [4] H. Hartmann, BIOmaterialien 2010, 11, 15–23.

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine