In 2011, people became ill, and some even died as a result of an EHEC outbreak—an intestinal infection caused by the enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli bacterium. The cause was fenugreek sprouts contaminated with these pathogens, which were consumed as vitamin-rich raw food. This extreme case highlights the importance of sterility in food products. In even more sensitive environments, such as hospitals, sterility is crucial to prevent hospital-acquired infections caused by pathogen transmission.

What Does Sterile Mean?

Sterilization aims to kill virtually all microorganisms and pathogens present in a solution, on solid surfaces, or in the surrounding air. These include bacteria, viruses, and spores, as well as infectious proteins such as prions, and plasmids and other pathogenic DNA fragments.

However, achieving 100% elimination of all microorganisms and pathogens is not possible in practice. Therefore, the success of a sterilization method is defined as the probability of reducing the number of viable microorganisms and pathogens below a threshold value. This is typically measured by the number of “colony-forming units” (CFU) still detectable after sterilization—the remaining number of viable microorganisms.

A material treated by a specific sterilization method is considered “sterile” when a reduction in germ count by at least a factor of 106 has been achieved. In practical terms, this means that, out of one million identically treated units, colony-forming units (CFUs)—i.e. viable germs—may only be detectable in one unit.

Sterile Work in Medicine and Research

In the production of medications or injection solutions, sterility must be maintained throughout the entire process. Similarly, in hospitals, it is essential to ensure that not only medications but also medical devices and instruments that come into contact with patients are sterile, to prevent pathogen transmission.

In medical, biological, and pharmaceutical research as well, constant sterility is a prerequisite for safe, error-free work and thus for correctly interpretable results. For example, if a bacterial culture is contaminated by foreign organisms, misinterpretation of results is inevitable.

To ensure sterile work under various conditions, different sterilization methods suitable for the respective material to be sterilized are available.

For instance, a heat-sensitive culture medium, such as that required for enrichment cultures to detect microorganisms, must be treated differently than a surgical instrument made of stainless steel, titanium, or tantalum.

Various Sterilization Methods for Practical Use

Sterilization methods are generally classified by their fundamental mode of action into physical and chemical methods. Physical methods include thermal sterilization, sterile filtration, and irradiation using UV or gamma radiation. Chemical methods include fumigation with ethylene oxide or formaldehyde.

Thermal Sterilization Methods

Thermal sterilization methods are divided into hot air sterilization and steam sterilization, also known as autoclaving. Both methods utilize the germicidal effect of heat.

Hot Air Sterilization

Hot air sterilization is performed in sterilization ovens using dry heat. The material is typically exposed to +180 °C for two hours. This method is particularly suitable for glass, metal, or porcelain equipment that can easily withstand such high temperatures.

Autoclaving

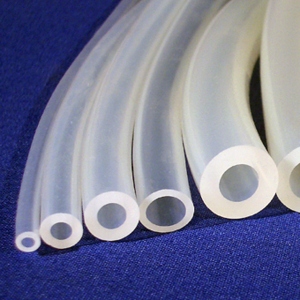

For nutrient solutions used to cultivate microorganisms and for plastic materials such as pipettes, syringes, or laboratory bottles, steam sterilization in an autoclave is the method of choice.

The operation of such sterilizers is comparable to that of a pressure cooker: in a sealed vessel equipped with a pressure relief valve, water is heated to +121 °C, generating a steam pressure of approximately 2 bar, and the steam displaces the air through the valve. The material to be sterilized is “autoclaved” under these conditions for a specified time, typically 20 minutes. This causes proteins and nucleic acids to denature, leading to the death of microorganisms and thus to sterilization.

Autoclaving is particularly effective for killing spores, especially bacterial endospores, because the moist air causes the resistant cell walls of the spores to swell, thereby reducing their thermal resistance. Spores are far less sensitive to dry heat.

Tyndallization

Tyndallization is a “fractional” sterilization method in which the material to be sterilized is heated to +100 °C several times and then incubated at approximately +30 °C for extended periods. The purpose of this procedure is to allow the dormant forms of microorganisms—the spores—to germinate between the heating steps. In this state, they lose their heat resistance and are killed during the subsequent reheating.

A significant disadvantage of this gentle method, which dates back to the Irish polymath John Tyndall (1820–1893), is the considerable time required. It is therefore no longer relevant for laboratory use but still has applications in the food industry.

UV and Gamma Irradiation

Microorganisms and pathogens are killed by exposure to UV or gamma radiation through radiochemical mechanisms. UV light in the wavelength range between 200 and 300 nm is used particularly for operating microbiological safety cabinets. These workstations, also known as laminar flow cabinets, are enclosed work tables equipped with a special ventilation system that continuously supplies sterile air to the work area while preventing particles—and thus germs—from the surrounding air from entering the workspace.

The antibacterial effectiveness of UV radiation on microorganisms and pathogens is based on energy absorption by DNA and RNA. The radiation causes irreversible chemical changes in these large biomolecules, damaging the microorganisms and pathogens and subsequently causing them to die.

Gamma irradiation also employs comparable radiochemical mechanisms that disable the functionality of microorganisms, viruses, and pathogens. Both irradiation facilities based on radionuclides such as cobalt-60 or cesium-137 and electronic radiation sources, including X-ray tubes, are used for this purpose. The latter offer greater radiation safety for operating personnel than continuously emitting radionuclide sources, as they can be switched off.

X-ray and gamma irradiation offer the advantage over UV irradiation of being able to penetrate matter and therefore remain effective even in packaged materials. They are primarily used for industrial sterilization of final-packaged and palletized in-vitro diagnostics (IVD) and other medical products such as syringes, surgical supplies, or dressings, which can be used immediately after irradiation.

Radioactive contamination of the treated material is completely impossible with X-ray and gamma radiation, as the material is merely exposed to higher-energy electromagnetic radiation that cannot cause changes to atomic nuclei and therefore cannot induce radioactive activation.

Sterile Filtration

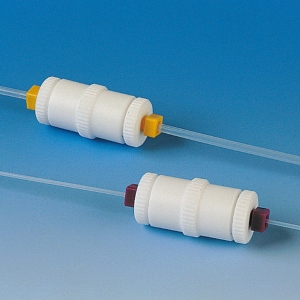

Some solutions, such as vaccines and liquid culture media, are heat-sensitive and cannot be sterilized by conventional heat sterilization methods. Sterile filtration is suitable for these applications, as it does not thermally stress the material. The solution is passed through sterile filters, usually membrane filters with a pore size of 0.2 µm, which microorganisms such as bacteria cannot pass through. Sterile filters are also used for decontaminating gases, for example when aerating sterile solutions or cultures.

Chemical Sterilization Methods

In addition to thermal methods, chemical sterilization methods are also used in practice, primarily for decontamination tasks in hospitals. For surfaces, such as hospital furniture or equipment, alcohols like isopropanol, as well as solutions of formaldehyde, peracetic acid, and phenols like m-cresol, are used. Their wetting ability is enhanced by the addition of detergents. Solutions of quaternary ammonium compounds, mainly used for household hygiene, also have germ-reducing effects. Microbicidal gases for textile disinfection, such as the treatment of hospital laundry, include ethylene oxide and formaldehyde gas, and less commonly chlorine gas, in appropriate dilutions.

Sterilization Methods in Everyday Laboratory Practice

The Robert Koch Institute (RKI) in Berlin, a central German federal institution whose primary tasks involve “the scientific investigation, epidemiological and medical analysis and assessment of diseases with high risk potential, high prevalence, or high public or health policy significance,” published an updated “List of Tested and Approved Disinfectants and Methods” in October 2017 (Bundesgesundheitsblatt 2017.60:1774-1297). These provide assurance of optimal results when used properly and professionally.

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine