Plastics are used in countless applications thanks to their versatile modifications and properties. They can be found in nearly every area of daily life, whether in a car, on a couch, or inside a refrigerator. One important property is permeability, meaning the ability to allow gaseous or liquid substances to pass through. Depending on the application, high permeation may be desirable, as in functional clothing, or no permeability at all may be required, such as in fuel tanks of vehicles.

The Path Through the Material

Permeability describes the ability of a material to permit permeation, derived from the Latin permeare, meaning to pass through or traverseand therefore the property of allowing gaseous and liquid substances to pass through a non-porous material. The greater the permeability, the higher the transmission rate of the material and the more easily foreign substances can pass through.

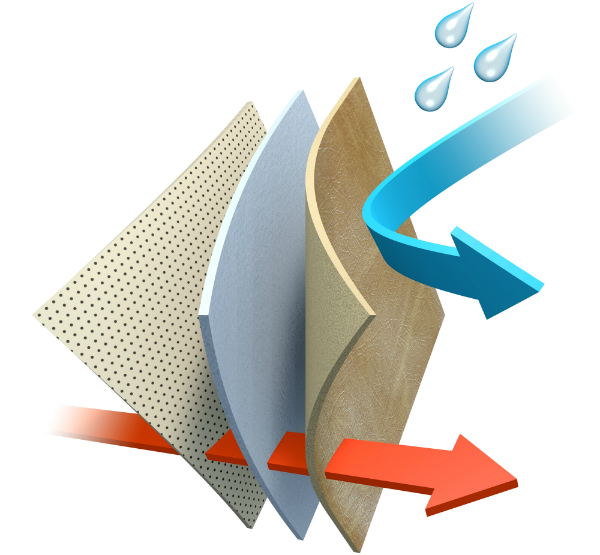

The process of permeation essentially consists of three steps:

- The adsorption of a foreign molecule on the surface of the material.

- The diffusion of the molecule through the material.

- The desorption of the molecule on the opposite side of the material.

In most cases, the second step, the diffusion through the material, is the rate-determining step. It determines how quickly permeation occurs. Since the concentration of the migrating substance is higher on one side of the material, permeation is a diffusion process.

This process can be described physically using the laws established by the German physiologist Adolf Fick (1829–1901). Diffusion can occur through various mechanisms, which is why four general models are distinguished:

- Molecular models

- “Free volume” models

- Empirical models

- Geometric models

Based on these different mechanisms, materials can be developed and adapted so that diffusion can be completely or partially prevented.

Units and Measurement of Permeability

There are several ways to specify permeability. A historical but today rarely used unit is the Barrer, named after the New Zealand–born English chemist Richard M. Barrer (1910–1996), and defined as follows:

![]()

More commonly used today are specifications such as the permeation coefficient C or the permeation rate P, which are related as follows:

![]()

The permeation coefficient C therefore refers to the length x that the substance must permeate through the material, the cross-sectional area A, and the partial pressure difference Δp.

When measuring permeability, both the material and the substance that is intended to diffuse through that material must be considered.

Different gases require different test procedures, meaning a general permeability value cannot be provided for a material. Permeability always refers to a specific material and a specific medium, such as the permeation of oxygen through polystyrene. In general, a relatively simple method is used for measuring permeability, and it is also applicable to plastics: The test material is placed inside a temperature-controlled permeation cell in such a way that it divides the cell into two halves. One half is flushed with the chosen test gas, e.g., oxygen, under a defined test pressure, while the other half is flushed with a carrier gas, usually nitrogen. When the test gas diffuses through the material and desorbs on the other side, it is absorbed by the carrier gas and can then be analyzed, for example by mass spectrometry.

The different test methods are precisely defined and established in DIN 53380-3 (German Institute for Standardization) for measuring oxygen permeation. For liquids, another method can be used, which is also specified in DIN, formerly DIN 53532, now DIN EN ISO 6179:2017. In this procedure, a test container is filled with a medium, sealed with the test material, and weighed. The container is then turned upside down, allowing the liquid to diffuse through the material.

After a defined period, the container is weighed again, and the mass difference reveals how much liquid has permeated the material.

The long test duration of more than 1,000 hours and the fact that this method is hardly suitable for materials with a very low permeability of <0.5 g/m² h-1 are two major disadvantages. However, if a carrier gas, similar to gas permeability testing, is used to transport the diffused liquid and analyze it via mass spectrometry, significantly more precise measurements down to 0.01 g/m² h-1 can be achieved. This also allows testing of liquid mixtures and possible effects of carry-over.

If the general permeability of a material needs to be evaluated quickly, a rapid test with helium as the test gas can be used. This noble gas diffuses particularly quickly and allows short measurement times. The results provide initial rough indications of material permeability.

Plastics and Polymers

Plastics, commonly referred to as “plastic”, are materials primarily composed of polymers and derive their properties from them. They constitute a major category of chemical compounds within the class of macromolecules. A distinction can be made between natural polymers, such as proteins, silk, and cellulose, and synthetic polymers, such as polyethylene, polyvinyl chloride, or celluloid. Both classes serve as important raw materials for further processing.

For processing and later use as a material, homopolymers consisting of only one monomer type, such as polypropylene, can be used, as well as copolymers consisting of different monomers, such as acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene, or mixtures. Polymers can also be amorphous or semi-crystalline, linear or highly crosslinked. These properties can change due to temperature or stress, further expanding their application range. Thus, very hard plastics like acrylic glass can be produced, as well as very soft and elastic rubbers.

Due to the large number of monomers and the many ways to chemically modify and combine them, polymers form a highly versatile and attractive class of materials found in nearly every sector.

Barrier Properties of Plastics

Permeability in plastics is based on the mobility of the polymer chains. The stiffer the chains are, the less permeable the material becomes and the lower its permeability. In this context, the glass transition temperature of the respective polymer plays a crucial role.

Below this temperature, the polymer chains stiffen, resulting in lower permeability. Above this temperature, the chains become more mobile and the polymer becomes more permeable. Therefore, care must be taken to ensure that the operating conditions are suitable so that permeation does not occur undesirably or is prevented. To improve barrier properties, there are generally three options:

- Vacuum coating with thin layers of aluminum, as used in TetraPak, aluminum oxide, or silicon dioxide.

- Incorporation of finely dispersed nanoparticles into the plastic matrix. These can improve polymer behavior and act as additional obstacles to gas transmission.

- Use of multilayer films suitable for sensitive technical applications or food packaging, consisting of inorganic and polymer layers applied to a flexible polymer substrate.

This makes it possible to develop plastics that are selectively permeable or impermeable to certain gases, tailoring them to the intended application.

Applications and Future Developments

Important application areas in which permeability plays a major role include packaging and seals. Packaging must, for example, prevent oxygen permeation in beer to ensure the aroma is not lost. In red wine, particularly in older vintages, oxygen permeation contributes to the development of specific flavor notes that are often described in flowery terms by connoisseurs.

Seals must not only keep liquids away but, in some cases, also prevent gas permeation, for example in gas supply lines, making them indispensable in plant engineering and thermal engineering.

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine