That blood is thicker than water is a common saying, and from a physical perspective it is not incorrect. However, when measured by its viscosity, blood does not behave according to the same rules as water. Instead, it exhibits a discontinuous flow behaviour. This makes this vital fluid a non-Newtonian fluid, in contrast to water, which behaves as an ideally viscous Newtonian fluid. An insight into the world of flowing matter.

Definition of Newtonian and Non-Newtonian Fluids

Liquids and gases can be divided into two fundamental classes according to their flow behaviour: Newtonian fluids and non-Newtonian fluids. The term goes back to Isaac Newton (1643–1727). The English physicist and mathematician described the viscosity of an ideal, or Newtonian, fluid in his law and thus laid the foundation for mathematically describing the behaviour of fluids.

In Newtonian fluids, the shear rate (also referred to as the rate of deformation) is proportional to the shear stress. The following equation applies and is known as the Newtonian law:

τ = η du/dy

η is a proportionality constant and is also referred to as the dynamic viscosity. According to this equation, the shear stress τ depends directly on the shear rate du/dy. Here, u is the flow velocity parallel to the wall and y is the spatial coordinate perpendicular to the wall.

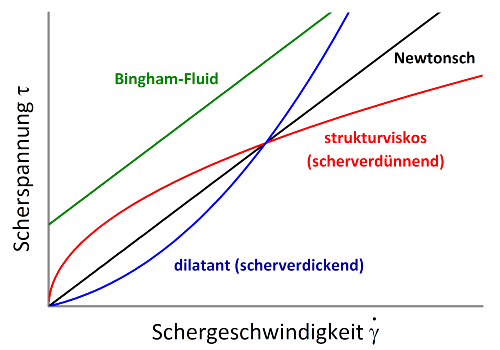

Such fluids therefore exhibit linearly viscous flow behaviour, meaning that the viscosity remains constant and independent of the applied load. Newtonian fluids display the simplest type of flow behaviour, and their motion can be described by the Navier–Stokes equations.

Most fluids encountered in everyday life are Newtonian fluids and behave in an ideally viscous manner. Examples include water, air, most solvents and gases, as well as many oils such as mineral oil.

What Are Non-Newtonian Fluids?

Rheology, also known as the science of flow, is the field that deals with the behaviour and flow mechanics of non-Newtonian fluids. A non-Newtonian fluid is defined as a fluid that does not exhibit ideal viscous behaviour.

Non-Newtonian flow behaviour can be attributed to changes in interactions within a fluid at different shear forces. For example, the interactions between particles in a suspension or emulsion change as the externally applied force varies, which in turn alters the viscosity of the system. As a result, most dispersions are not ideally viscous.

Properties of Non-Newtonian Fluids

The viscosity of non-Newtonian fluids may either decrease with increasing shear force, in which case they are referred to as shear-thinning or pseudoplastic, or increase, which is described as dilatant behaviour. Shear-thinning behaviour, i.e. a decrease in viscosity with increasing shear rate, is far more common than dilatant behaviour. Examples of shear-thinning fluids include dispersions and molten polymers. Dilatant or shear-thickening behaviour occurs, among other cases, in starch–water mixtures or wet sand.

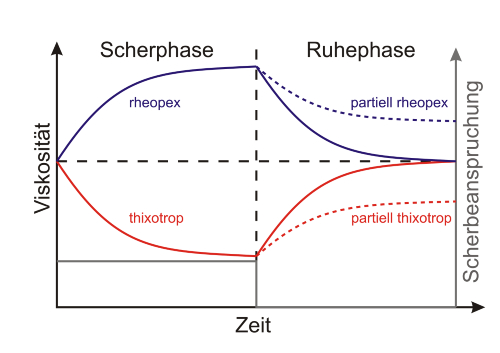

If the viscosity returns to its original value only with a time delay after a reduction in shear force, this is referred to as thixotropy (delayed increase in viscosity) or rheopexy (delayed decrease in viscosity). After some time, these fluids usually return to their initial viscosity. If this does not occur, the behaviour is described as partial or false thixotropy or rheopexy.

Another distinguishing feature of non-Newtonian fluids is whether they exhibit a yield stress. Fluids with a yield stress are referred to as plastic fluids. These substances initially behave like solids and only begin to flow when stronger shear forces are applied. The transition point from solid to liquid is known as the yield stress. At a shear rate of zero, the viscosity of these fluids is infinitely high. Semi-solid substances such as ointments or creams exhibit a yield stress and therefore do not behave in an ideally viscous manner.

In the simplest case, a plastic fluid behaves as a solid up to a certain shear force and as a Newtonian fluid above that threshold. Such systems are known as Bingham fluids. Examples include ketchup, mayonnaise, toothpaste, yeast dough and some wall paints.

A Casson fluid is a plastic fluid that becomes capable of flowing above a certain shear stress and subsequently exhibits non-Newtonian properties, as can be observed, for example, in chocolate mass.

Examples of Non-Newtonian Fluids and Their Applications

A list of examples of well-known substances with non-Newtonian flow properties:

- Most dispersions

- Slurries

- Granulates

- Polymer melts

- Lubricants and greases such as sliding greases, multipurpose greases and high-temperature PTFE greases

- Sprays

- Adhesives

- Blood

- Ointments and creams

- Doughs and starch–water mixtures

- Ketchup, mayonnaise, pudding

- Glycerine

- Cement slurries

- Quicksand

Non-Newtonian Fluids with Shear-Thinning Behaviour

A well-known shear-thinning fluid with a yield stress is wall paint. It adheres to the roller as an elastic solid and only liquefies when the shear forces generated by pressing the roller against the wall become large enough to exceed the yield stress.

Ketchup liquefies when force is applied, for example by shaking, tapping or stirring, and then becomes flowable. When at rest, however, it quickly returns to its original state. It therefore exhibits thixotropic flow behaviour.

As early as the Middle Ages, a blood-like fluid with non-Newtonian behaviour was produced. This was achieved by mixing iron(III) chloride and calcium carbonate, in the form of crushed eggshells, with water. The resulting mixture is initially a reddish-brown gel, but turns into a blood-red liquid when shaken. When left to stand, it reverts to a gel. This process can be repeated indefinitely. This thixotropic effect is thought to be the basis of so-called “blood miracles”, such as that of Saint Januarius of Naples.

The shear-thinning behaviour of polymers in solutions and melts is of particular technical importance. The polymer chains are entangled with one another, and at higher shear pressures these entanglements are released, causing the viscosity to decrease. As a result, thin-walled injection-moulded parts made from thermoplastics can be produced with lower pressure than thick-walled components.

Non-Newtonian Fluids with Dilatant Behaviour

When starch is mixed with water, the mixture initially remains liquid when stirred slowly. With more vigorous stirring, it forms an increasingly thick paste that can eventually become crumbly. These crumbs, however, quickly become liquid again and rejoin the rest of the paste (rheopexy).

A similar behaviour can be observed with quicksand, which has a low viscosity during slow movements. If an attempt is made to pull out a submerged object quickly, the viscosity increases and it becomes impossible to remove it from the quicksand. This occurs because stronger forces squeeze the water out of the sand–water mixture, leaving behind sand particles with a much higher viscosity.

Dry sand also exhibits rheopectic properties. Example: a rod is placed in a bucket, which is then filled with dry sand. Tapping the bucket compacts the sand. If an attempt is then made to pull the rod upward, shear forces act on the sand and the grains interlock. The bucket can now be lifted. After some time, however, the sand grains loosen again and can slide past one another, the rod comes free and the bucket falls down.

Commercial products that make use of dilatant properties include, for example, bouncing putty or “Active Protective System” (APS) inserts in protective clothing. Bouncing putty becomes solid under strong pressure, such as when thrown onto the ground, and rebounds in a rubber-like manner. It can also be torn and shattered. When left undisturbed for some time, however, it flows like a viscous liquid. APS inserts are used in motorcycle clothing and consist of pads with dilatant mixtures that do not restrict mobility. In the event of sudden force, such as during a fall, the material hardens and the forces are distributed over a larger body surface.

Image Sources: Cover image | © vittaliya – stock.adobe.com Painting of Sir Isaac Newton | © James Thronill after Sir Godfrey Kneller, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Graphic: Thixotropy and Rheopexy | © David Spura, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons Graphic: Shear stress and shear rate | © Dietmar Haba, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons Ketchup bottle pouring | © New Africa – stock.adobe.com

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine