Plastics have become indispensable in modern everyday life. As versatile materials, their properties can be tailored to meet a wide range of requirements. The discovery of the structure and architecture of plastics — and thus their rise as universal materials — goes back to the chemist Hermann Staudinger (1881–1965). In 1953, he was awarded the Nobel Prize “for his discoveries in the field of macromolecular chemistry.” The term for the synthetic materials we now know as plastics has a rich historical background. In the early 20th century, the German chemist Ernst Richard Escales (1863–1924) founded a specialised journal titled Kunststoff, which helped establish the scientific understanding of these groundbreaking materials. First published in 1911, the journal remains an important technical publication in the field of materials science.

Classification and Properties of Plastics

Mechanical–thermal behaviour is used to classify plastics into thermosets, elastomers, and thermoplastics.

Thermosets

The tightly meshed, three-dimensional network of macromolecules gives thermosets their hardness and brittleness and makes them resistant to high temperatures.

As with all other plastics, chemical resistance depends on composition. Epoxy resins are well-known, widely used thermosets noted for their robustness. Bakelite, in turn, is the trade name for one of the first thermosets, produced on the basis of phenolic resins.

Elastomers

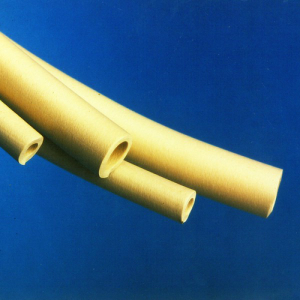

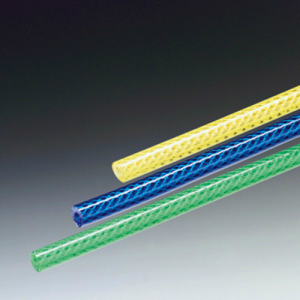

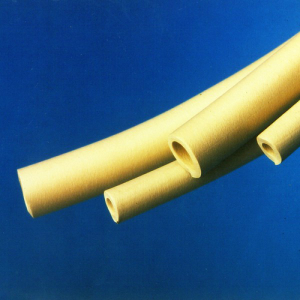

Elastomers consist of macromolecules crosslinked with a wide mesh. They deform under tensile or compressive load and return to their original shape once the external force is removed. Natural rubber is a well-known representative of the elastomer group and is used primarily in the production of car tyres. It is also used to manufacture chemical hoses or round cords that serve as the basis for seals.

Before natural rubber can be used technically, it must be pre-treated. Vulcanisation increases the sulphur content in the material, thereby improving, among other things, chemical resistance to diluted acids, alkalis, and mineral oils.

EPDM (ethylene-propylene-diene rubber), NBR (acrylonitrile-butadiene rubber), and CR (chloroprene rubber) are examples of synthetic rubbers. In part, they exhibit greater chemical inertness to acids and alkalis than natural rubber and are therefore preferred for transporting more aggressive media.

Thermoplastics

Thermoplastics consist largely of unbranched, linear macromolecules that can be plastically deformed when heat is applied and retain their shape upon cooling. The process is reversible, and the material can be reshaped when reheated. The best-known thermoplastics include polyethylene (PE), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polystyrene (PS).

What Is Meant by “Chemical Resistance”?

A material’s resistance or durability can in principle relate to various properties, such as mechanical, thermal, or weather resistance. Chemical resistance refers to the ability of a material to withstand exposure to different chemicals. In practice, people often distinguish between “chemically resistant,” “conditionally chemically resistant,” and “chemically non-resistant.” A material is chemically resistant if it remains unharmed during prolonged contact with a chemical — that is, its physical, chemical, and mechanical properties remain unchanged.

The term chemically inert is often used as a synonym.

A material is chemically non-resistant if, upon contact with a chemical, it loses its typical properties after a very short period, whereas it is conditionally chemically resistant if it retains its properties over a defined time interval. This can also mean that the resistance is sufficient for the intended use. A material’s resistance is temperature-dependent, which must be considered in application.

Inertness of Plastics

Chemicals to which a plastic is not resistant cause the material to swell or soften. Whether the chemicals involved are aggressive media such as acids, alkalis, or organic solvents; aggressive gases such as chlorine; or comparatively “mild” substances such as mineral oils — the mechanism is always the same: molecules of the acting chemical diffuse into the plastic and loosen the weak interactions between polymer chains.

In some cases, this leads to the formation of microcracks in the material, which grow under higher mechanical loads and eventually result in macroscopic cracks. This phenomenon is known as stress cracking. Because diffusion is temperature-dependent, the chemical resistance of plastics decreases as temperature rises.

Test Methods and Standards Framework for Assessing the Chemical Resistance of Plastics

Various methods are available to measure the durability and chemical resistance of plastics. EN ISO 175:2010 describes, for example, “test methods for determining the behaviour of test specimens in liquid chemicals.” In this method, the test specimen is placed in the liquid chemical and the changes to the plastic are then measured. EN ISO 22088-6:2009 sets out additional procedures for determining so-called environment-induced stress cracking. Here, the plastic specimen is subjected to an external stress or pressure and the changes are measured. The ESC test (environmental stress cracking) and the constant-load tensile test are two common methods.

Finally, the procedures described in ISO 2812-1 and ISO 2812-2 provide two further options used in chemistry and industry to assess the resistance of plastics.

In these tests, the surface condition of the plastic is evaluated microscopically after either immersion in the chemical or application of the chemical onto the surface. After a defined period, the microscopic evaluation is carried out to assess whether, and to what extent, detachment, discolouration, or swelling has occurred. In practice, these tests help users — and especially manufacturers — to assess the properties of plastics very precisely and select a suitable material for a given application.

Where Is Chemical Resistance Particularly Important?

The suitability of a plastic always depends on the specific application. For many uses, chemical resistance plays a key role. For example, when transporting chemicals through hose lines — especially aggressive media — only elastomers with appropriate chemical resistance can be used. The same applies in other industrial sectors where it is crucial that the elastomers used for seals exhibit sufficient chemical durability.

Thus, in the petroleum-processing industry they must be resistant to mineral oils, whereas in the pharmaceutical or chemical industries they need to be inert primarily to acids or organic solvents.

Popular Materials and Elastomers

Among the plastics based on fluorinated hydrocarbons is FPM/FKM (fluoroelastomer), also known under the trade names Viton®, Iso-Versinic®, or THOMAFLUOR. It is inert to solvents, oils, and hydrocarbons. It is used for hoses as well as in the form of round cords, O-rings for seals, and as stoppers.

The best-known plastic in this group is PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene). Also known as TEFLON®, this material is unmatched in terms of resistance to chemicals and solvents. It is therefore used wherever particularly aggressive media are involved. Other well-known materials are synthetic rubbers such as EPDM (ethylene-propylene-diene rubber) or NBR (acrylonitrile-butadiene rubber). These are sometimes used in combination — for example, EPDM with PP (polypropylene) — for chemical hoses.

To select the appropriate material for a given application, one should always consult chemical resistance lists. Most suppliers of plastics and materials provide these, making selection easier for the user.

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine