In plant and mechanical engineering, in drive technology, or in precision mechanics, information on the friction behavior of the materials used is essential, with the coefficient of friction being a key criterion. In motors, gear units, compressors, and hydraulic systems, various machine and drive elements such as plain and rolling bearings or gear drives operate with different materials moving against each other. Other areas, such as sealing technology—relevant, for example, for pumps—likewise demand truly frictionless operation. Undesired friction inevitably leads to wear of components, which can ultimately result in loss of functionality of the machinery involved.

It is therefore not surprising that this leads to economic losses worth billions every year. Some estimates suggest a macroeconomic impact of five to eight percent of the gross domestic product. This makes it worthwhile to take a closer look at how such losses can be reduced and what role modern polymer materials play today.

Tribology – the Science of Friction and Wear

According to today’s accepted scientific definition, tribology is “an interdisciplinary field aimed at optimizing mechanical technologies by reducing friction- and wear-related energy and material losses.” The withdrawn German standard DIN 50320:1979-12 defined it in greater detail as the “science and technology of interacting surfaces in relative motion,” covering the entire field of friction and wear, including lubrication, and the effects at the interfaces between solids as well as between solids and liquids or gases.

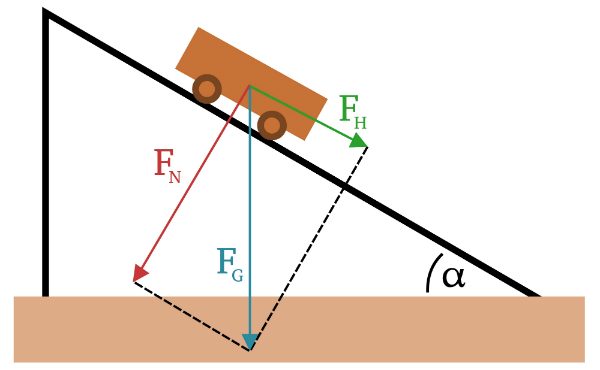

When two bodies are set into motion relative to each other, different forces act on them. Perpendicular to the contact surface acts the normal force, also known as the contact pressure. The force opposing the direction of motion is the frictional force. A distinction is made between static friction, which acts on stationary bodies, and sliding friction, which occurs at the contact surfaces of bodies moving relative to each other. Frictional force arises due to surface irregularities and the cohesive forces between molecules on the interacting surfaces.

Friction is therefore not a material property; it is determined by the material pairing, the surface characteristics of the sliding partners, and the normal force acting on them.

The coefficient of friction—also known as the friction coefficient—defines the ratio of frictional force to normal force. It can be experimentally determined for different material pairings using tribometers. The coefficient of friction, including the friction coefficient of plastics, depends not only on the material pairing and surface roughness but also on the temperature of the sliding surfaces, the sliding speed, and the normal load.

Polymer Materials in Tribological Applications

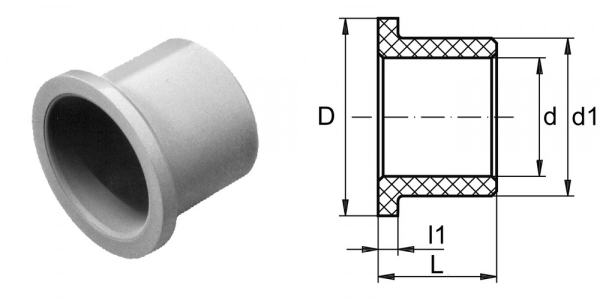

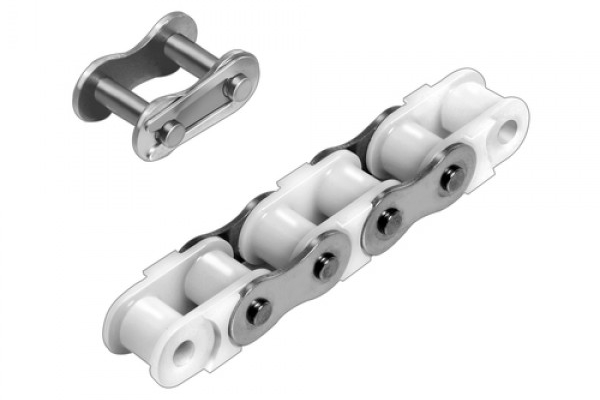

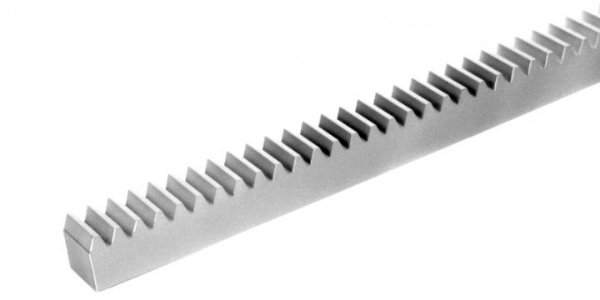

The use of plastics in components subject to friction and wear has grown significantly in recent years, as they offer advantages over purely metallic components in specific cases. In transport systems—such as gears and sprockets—and in plain or ball bearings, plastic bushings often outperform metallic counterparts because they require no lubrication. The same applies to applications where boundary or mixed friction occurs and a fully formed lubrication film cannot be guaranteed.

This effect is observed, for example, in bearings with fluctuating rotational speeds. Depending on the application, additional material properties may be required—such as chemical and mechanical resistance, abrasion resistance, electrical insulation, or damping behavior. Plastics also offer economic advantages, as many components can be produced more cost-effectively than metal parts.

The Right Material Combination – Plastic/Metal or Plastic/Plastic?

In practice, numerous drive or sealing elements are made from combinations such as metal/metal, plastic/metal, or plastic/plastic. The focus here is on the latter two. Which combination is best for a given application? The coefficient of friction of plastics is an essential parameter, and additional reference values include the maximum allowable surface temperature and, for dynamically loaded bearings, the pv value (the product of surface pressure and average sliding speed). These values are not inherent material properties and must be determined for each pairing. For many combinations, experimentally determined data is already available in reference tables.

This allows an initial assessment of suitable materials—such as PTFE, POM, or PET—once operating conditions like sliding speed, temperature, and load are known.

Plastic/Metal

Plastic/metal pairings are widely used because heat can be dissipated efficiently through the metallic partner while the plastic component can be tailored to the application. Plastics such as PTFE or POM are suitable for high sliding speeds, as sliding surface temperature is a key wear factor and these materials tolerate the heat generated during operation. On the metal side, hardness and surface quality must match the plastic. Generally, high hardness (HRc > 50) is advantageous to avoid early wear. With softer metals, surface asperities may break off and embed into the plastic, acting like abrasives.

The influence of metal surface roughness on the coefficient of friction depends on the polymer material: smooth surfaces are ideal for non-polar plastics such as PTFE or PET. For polar materials like polyoxymethylene (POM), very smooth metal surfaces promote adhesion and the formation of bonding bridges, increasing friction and potentially causing wear. A friction coefficient that may be ideal under other conditions becomes less favorable. Reference values for the surface roughness of metal sliding partners in combination with different plastics should therefore be considered. The load applied also affects wear, meaning the pv value must be taken into account as well.

Plastic/Plastic

In plastic/plastic systems, adhesion forces between the surfaces are the dominant factor. Sliding surface temperature and the associated frictional heat tend to be higher than in other pairings. Although their load capacity is lower, these systems offer advantages when chemical inertness, electrical insulation, or good damping characteristics are required.

Lubricants remain an important measure for optimizing friction coefficients and friction behavior in all material pairings. A lubrication film reduces friction; however, surface changes may occur due to chemical or physical reactions with the lubricant and its additives. Self-lubricating plastics, which require no lubrication, offer economic and environmental benefits.

Low-Friction Sealing Technology

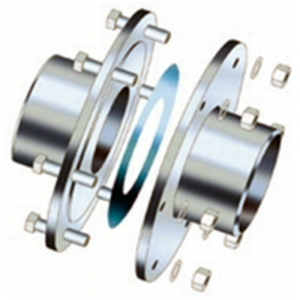

Another area in which both the coefficient of friction and the friction behavior of materials play a central role is sealing technology. Different sealing materials—such as FFKM, PVC, or silicone rubber—must meet specific requirements depending on the application.

In static seals, such as flat gaskets made from PVC or O-rings made from FFKM, friction is less critical; contact pressure and material resistance are more important. In dynamic sealing, however—when flat gaskets or O-rings are used for axial, rotating, or oscillating movements—the frictional behavior of the plastic again becomes crucial.

A low coefficient of static friction is also desirable to prevent the so-called stick-slip effect—jerky sliding that can occur during frequent restarts. Material resistance to the lubricants used must also be considered. Suitable choices include PTFE O-rings or FFKM O-rings due to their broad chemical resistance, as well as silicone rubber O-rings when physiological safety is required, for example in pharmaceutical or food-processing environments.

A low coefficient of static friction is also desirable to prevent the so-called stick-slip effect—jerky sliding that can occur during frequent restarts. Material resistance to the lubricants used must also be considered. Suitable choices include PTFE O-rings or FFKM O-rings due to their broad chemical resistance, as well as silicone rubber O-rings when physiological safety is required, for example in pharmaceutical or food-processing environments.

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine