How Hot Is It Really?

The air that surrounds us everywhere affects our comfort and well-being through its temperature. If it is too hot or too cold, we feel uncomfortable. That is why we regularly measure room temperature in order to regulate the indoor climate by heating or using air conditioning. When cooking or baking, or when measuring fever, temperature is also a familiar quantity – just as it is in many technical applications or laboratory environments. To ensure that chemical reactions proceed in a defined manner or to produce accurate and reliable analytical results, it is necessary to monitor and maintain specific values.

Important – Measurement Accuracy

To assess whether a thermometer is suitable for a specific application, its measurement accuracy must be considered. It is an important indicator of the quality of the reading and reflects the level of confidence in the displayed temperature values.

What Is Measurement Uncertainty?

A thermometer’s ability to provide readings close to the true value is called accuracy. It represents the positive expression of the measurement uncertainty inherent to every measuring device.

Manufacturers therefore use accuracy to describe the quality of their sensors.

Measurement uncertainty stems partly from systematic errors inherent to the device. These can cause positive or negative deviations from the true value. The magnitude of these errors can be derived theoretically or determined experimentally by calibrating a thermometer. Based on the determined deviation, which can be specified as a correction value in a measuring device or in an associated calibration certificate, these errors can be corrected mathematically.

Precision, on the other hand, describes an average and random uncertainty of results. This is based on the statistical dispersion of values and is represented by the measurement uncertainty interval. The size of this interval can be calculated from repeated readings with identical thermometers and comparable measuring conditions using the standard deviation u.

The uncertainty interval U is often specified as twice the standard deviation of the obtained measurements. Statistically, 95.4% of all temperature values determined correctly under specified conditions lie within this range. The uncertainty interval is always given as a difference from a mean measured value x0, for example +22 ±3 °C. In this case, the true temperature is most likely between +19 and +25 °C.

The requirements for determining and evaluating measurement uncertainty in laboratory measurement processes are described in the internationally recognized technical standard ISO/IEC Guide 98-3:2008-09: Measurement uncertainty – Part 3: Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement.

Factors Influencing Measurement Uncertainty

Uncertainty initially depends on the chosen measurement method and therefore on the thermometer used. For measuring body temperature, one can use a glass thermometer (which determines temperature via the expansion of alcohol in a capillary), a digital resistance thermometer, or an infrared thermometer. Each of these devices, due to its design, has a typical error and delivers readings of varying accuracy.

For technical applications with temperatures up to approx. +300 °C, resistance thermometers usually provide significantly more accurate results than thermocouples.

In addition, correct use of the method as well as proper handling and reading of the measuring device are crucial. Especially with classical glass thermometers or analog pointer devices, reading errors can easily occur.

Contact thermometers, such as glass and resistance thermometers, require a sufficiently large contact area with good thermal conductivity between the object and the thermometer for accurate measurements. This and a range of other potential sources of error can lead to deviations, causing the measured temperature to differ significantly from the true temperature.

Electrical Temperature Measurement in the Laboratory

In laboratory environments, resistance thermometers are frequently used for precise measurements. They are part of a measurement chain consisting of the temperature sensor, a connected transmitter, evaluation electronics or a display device, and the necessary connectors and cables. All of these components – including the connectors and cables – influence the accuracy. Each thermometer exhibits a systematic deviation from an ideal thermometer or a standardized thermometer characteristic curve.

For resistance thermometers, these characteristic curves are described in the standard EN 60751, which defines tolerance classes with maximum permissible deviations. For example, Pt 100 thermometers with the highest tolerance class A must not exceed an error of 0.2 K at +22 °C.

Signal transmission and processing in the connected measuring device have a certain uncertainty, and the display is not completely linear. In addition, all sensors undergo aging, which causes a gradual drift in sensitivity. As a result, improper measuring conditions or unstable ambient environments can lead to signal deviations.

Even insufficient immersion depth of a temperature sensor in the medium being measured can lead to heat dissipation errors. Likewise, an overly short measuring duration can cause an equilibration error, typically resulting in values that are too low. The latter mainly results from the thermal inertia of the measurement and the heat capacity of the thermometer.

Specific Sources of Error in Electrical Temperature Measurement

Resistance thermometers require a measuring current that heats the sensor slightly, resulting in a slightly higher displayed value. This error can be reduced by using the lowest possible measuring current and short measurement times. Furthermore, the line resistance and input resistance of the measuring device can cause errors, which can be minimized through proper circuit design and the selection of devices with high input impedance.

Temperature monitoring using thermocouples is based on comparing a measured thermoelectric voltage with a reference temperature, for instance 0 °C. The stability and accuracy of this reference temperature have a major influence on the correctness of the reading.

Additionally, the thermocouple or compensating cables used to connect to a measuring device exhibit typical temperature-dependent deviations similar to those of the thermocouple itself.

Differences in material at connection points between the sensor, reference junction, and measuring device can also generate additional thermoelectric voltages that lead to measurement errors.

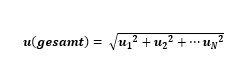

Based on all sources of error, the total error of a temperature measurement can be calculated from the sum of the individual errors (u1, u2, … un) in a given measurement chain.

Mathematically, the uncertainty of a measurement chain u(total) can be expressed as follows:

To determine measurement errors, temperature sensors must be checked regularly. During this calibration process, systematic deviations are determined by comparison with a thermometer of known accuracy. This makes it possible to correct the inaccuracy of the display or to adjust the instrument accordingly.

Essential – Instrument Monitoring

In technical applications and laboratories, temperature sensors are often used as testing instruments that must meet specific accuracy requirements. To ensure this, these thermometers must be calibrated as part of regular instrument monitoring. For this purpose, reference thermometers or reference standards are commonly used to ensure traceability of temperature measurements to national or international reference standards.

To guarantee this, reference thermometers used must be certified by accredited calibration laboratories recognized by the DAkkS. The certification must be verified and renewed regularly.

The Right Measurement Method for Every Temperature

While an alcohol-filled thermometer with a measuring range from -10 °C to +40 °C is sufficient to determine room temperature, temperatures below -18 °C are required for the storage of frozen food, and fever thermometers cover only the range between +36 °C and +42 °C. The requirements for temperature sensing in both scientific and technical contexts are far broader.

In glass industry melting furnaces, for instance, temperatures around +1000 °C must be measured, while metallurgical processes can reach even higher levels. Medical samples such as cell and gene material are stored in biobanks at -155 °C, and in physics laboratories dealing with superconducting materials, temperatures of interest are often below -250 °C. Technically, however, every temperature measurement is subject to error.

Such systematic errors can be detected and minimized with varying levels of effort. When choosing a measurement method, not only the purpose of the measurement and the resulting measuring range but also the required measurement accuracy are decisive factors.

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine