Corrosion is a global problem. Steel structures in particular are affected, such as bridges and load-bearing structures, but also industrial plants, railway tracks, pipelines, vehicles, and machinery. In 2009, the “World Corrosion Organization” (WCO) estimated the worldwide economic damage caused by corrosion at 1.8 trillion US dollars.

Corrosion and Its Formation

In the broadest sense, corrosion is a physico-chemical process in which a material reacts with components of its surrounding environment, thereby changing its fundamental properties. Corrosion is therefore primarily an environmentally induced phenomenon.

However, corrosion does not affect metals alone; non-metallic materials such as ceramics and glass are also subject to corrosion. Early and historically valuable stained-glass windows in churches are particularly affected. In this case, corrosion is based on ion exchange processes. Over long periods of time, these processes cause structural changes in the material, which can ultimately result in complete destruction.

In common usage, however, the term “corrosion” usually refers to metals. It is defined in the international standard DIN EN ISO 8044 as “… a reaction of a metallic material with its environment that causes a measurable change in the material (corrosion phenomenon) and may lead to impairment of the function of a component or an entire system (corrosion damage)“.

Corrosion is based on different reaction mechanisms. In most cases, corrosion is an electrochemical process, but chemical reactions and metallurgical phenomena can also cause corrosion.

Electrochemical Corrosion

Electrochemical corrosion is associated with the formation of a galvanic element. In such a galvanic element, two different metals, two electrodes—anode and cathode—are immersed in an aqueous electrolyte, between which an electrical potential is established. If both electrodes are connected via an electrical conductor, an electric current flows. In this process, the less noble electrode, the anode, dissolves.

This principle is applied in batteries and is also the cause of electrochemical corrosion of metals.

In electrochemical corrosion, the electrodes are either provided by different components of a metal structure or by inhomogeneities within a metal alloy. The electrolyte is usually penetrating water, for example rainwater, which can form a “short-circuited“ galvanic element. The consequence is the progressive electrochemical dissolution of the anodic metal component, which ultimately leads to loosening of metal joints or to corrosion within the metal itself, known as pitting.

One example of corrosion is the formation of rust on iron, a mixture of iron oxides. Iron rusts in the presence of water and dissolved oxygen. At one location on the iron surface, which acts as the anode, iron is oxidized to Fe2+ ions:

Fe → Fe2+ + 2 e− (anodic reaction)

At another location on the iron surface, which acts as the cathode, oxygen is reduced with the formation of OH− ions:

O2 + 2 H2O + 4 e− → 4 OH− (cathodic reaction)

Both electrodes are short-circuited via the surface of the iron. The electrons formed flow through the metal from the anodic to the cathodic area. The Fe2+ and OH− ions formed migrate through the water that has penetrated the structure and react to form iron(II) hydroxide Fe(OH)2. In the presence of oxygen, moist iron(II) hydroxide is further oxidized to hydrated iron(III) oxide Fe2O3 · x H2O, the corrosion product known as rust.

Chemical Corrosion

Chemical corrosion refers to the reaction of metals with oxidizing agents based on chemical processes. In this case, the direct reaction of metals with oxygen is dominant—it “oxidizes“ the metal and forms a metal oxide. However, corrosion by oxygen does not always result in damage, such as the scaling observed during iron processing.

Reactions with atmospheric oxygen can also lead to the formation of oxide layers on the surface, which protect the underlying metal from further chemical attack. This is referred to as passivation. A well-known example is aluminum, which is corrosion-resistant because it is protected by a surface layer of aluminum oxide (Al2O3) of the corundum type. This chemically largely inert layer is only a few nanometers thick; however, it can be further reinforced by electrochemical oxidation, known as “anodizing“. The layer is dense and adherent, allowing even concentrated nitric acid to be stored in aluminum tanks.

Other metals such as copper, lead, or tin also form oxidic surface layers. The properties of this surface layer determine whether the corrosion process initiated by surface oxidation continues or comes to a halt. If the layer is loose or porous and therefore permeable to oxygen and water, corrosion can penetrate deeply into the metal.

In addition, both inorganic and organic acids can cause chemical corrosion by dissolving the protective oxide layer and the metal itself. In combination with water, halogens such as chlorine and acid anhydrides such as sulfur dioxide (SO2) can also trigger corrosion through chemical reactions.

Metallurgically Induced Corrosion

The causes of metallurgically induced corrosion are found in structural changes of metals due to external influences. Owing to modern metallurgical knowledge, particularly alloying with small amounts of other metals, this form of corrosion now plays only a minor role.

A striking example of metallurgically induced corrosion is tin pest, which affected objects made of pure tin in earlier times. These included mainly organ pipes in churches, but also household utensils and decorative items made of tin.

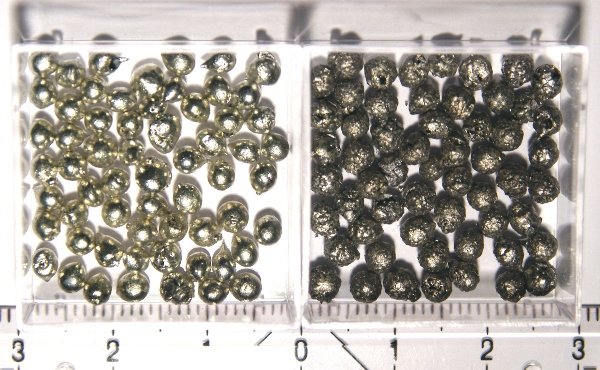

The reason is that tin exists under “normal“ conditions in two different modifications, α-tin and β-tin. A third modification, γ-tin, exists only above +162 °C. The two modifications α-tin and β-tin have completely different crystal structures, which are reflected not only in their appearance but also in their densities. At +20 °C, the density of α-tin is 5.75 g/cm3 and that of β-tin is 7.27 g/cm3. Each modification is physically stable only within a specific temperature range: gray α-tin below +13.2 °C, and silvery β-tin above +13.2 °C.

When the temperature falls below +13.2 °C, β-tin gradually transforms into α-tin. The lower the temperature, the faster the transformation proceeds. During this process, α-tin occupies a larger volume than β-tin. As a result, the metal gradually loses its structure, strength, and external shape in cold conditions and eventually disintegrates into a gray powder. The term “tin pest“ originates from a time when this form of metallurgical corrosion was not yet understood and was compared to the relentless plague outbreaks that repeatedly afflicted humanity.

Noble Metals and Base Metals – What Does That Mean?

In aggressive environments, metals corrode predominantly by chemical means. Exceptions are only the noble metals gold and silver, as well as the platinum metals ruthenium, rhodium, palladium, osmium, iridium, and platinum.

Due to their inherent chemical passivity, noble metal coatings provide very reliable corrosion protection for metals, but are usually not economically feasible.

In the context of metals, the terms “noble“ and “base“ have not only a value-related meaning but also a physico-chemical background that is important for understanding the different corrosion tendencies of metals. The decisive factor is the respective “electrical potential“. Simplified, this is the voltage that develops in a galvanic cell between a hydrogen electrode and a metal electrode.

The hydrogen electrode is a platinum electrode surrounded by hydrogen gas, which adsorbs hydrogen in small quantities. The reaction H2 ⇄ 2H+ + 2 e− takes place at this electrode. For practical reasons, the potential of the hydrogen electrode is set to zero, so that the potentials of metals relative to the hydrogen electrode can assume both negative and positive values. The higher the potential of a metal relative to the hydrogen electrode, the more noble it is. If metals are arranged according to their standard potentials from highest to lowest, the so-called “electrochemical series“ is obtained, which can be represented in abbreviated form for the most important metals as follows:

(−) Li → K → Na → Mg → Al → Zn → Fe → Sn → Pb → Hydrogen → Cu → Ag → Hg → Pt → Au (+)

This also explains why copper (Cu) and mercury (Hg) are sometimes counted among the noble metals: both have a positive standard potential.

When more noble metals are alloyed with base metals, the standard potential shifts to higher values, and the tendency to corrode is consequently lower than that of the base metal main component. In this way, high-alloy stainless steels—iron alloys containing nickel, molybdenum, and other metals—achieve qualities that are comparable in many respects to those of noble metals.

Corrosion – Also an Environmental Problem

Corrosion is not only a problem in the chemical industry, where plants and pipelines are attacked and corrode due to aggressive media. It is also an environmental problem, because worldwide, hardly localized pollution loads the atmosphere with chemically reactive substances. These include nitrogen oxides from emissions of large combustion plants and automotive traffic, which are converted through reaction chains into nitric acid (HNO3), as well as sulfur dioxide (SO2), which mainly originates from the use of sulfur-containing fossil fuels and leads to the formation of sulfurous acid (H2SO3).

Both pollutants are washed out of the atmosphere by precipitation and become corrosively active, which inevitably leads to long-term damage to bridges and other steel structures.

Corrosion Protection in Practice

Corrosion is irreversible and therefore causes considerable costs when corrosion damage has to be repaired. It is therefore economically necessary to take effective preventive measures in advance in order to avoid corrosion.

Preventive measures include selecting the right materials for the respective application. For example, copper gutters can only be fastened using gutter brackets made of the same metal, copper, because using other metals would quickly lead to the formation of local galvanic elements with rainwater, initiating electrochemical corrosion. Similar problems can also arise with different metals that are riveted together.

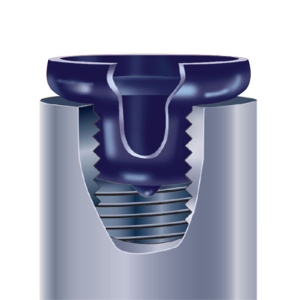

The safest approach is to prevent local elements that trigger electrochemical corrosion by interrupting conductive connections between different metallic components, for example by using electrically insulating coatings, plastics, or ceramics. For connecting metallic components, spacers, bushings, and screws made of plastics or ceramics are suitable. In addition, access of atmospheric oxygen and moisture can be reduced by paint coatings or by greasing, as is common practice with so-called terminal grease on the contacts of lead-acid batteries in motor vehicles.

Another very effective method is the use of a “sacrificial electrode“ made of a less noble metal than the metallic material to be protected. This variant of corrosion protection is primarily used in industrial applications. These include, for example, underground oil and fuel tanks or steel gas pipelines. An electrically conductive connection is established to a zinc or magnesium plate, which is embedded in the moist soil in close proximity and thus effectively forms a galvanic cell. In this so-called “cathodic corrosion protection“, the less noble metal, the sacrificial electrode, gradually dissolves anodically over a long period of time, while hydrogen is released at the metal component to be protected. As long as the sacrificial electrode has not been consumed and the resulting small current flow is not interrupted, corrosion protection remains effective.

The decision in favor of a particular protective measure—of which there are many more than those presented here—depends not only on the technical possibilities for implementation but also on the required service life of the metal structure to be protected. For a tin can, a single application of lacquer or plastic coating on the interior is sufficient to adequately guarantee the only briefly required corrosion protection. For railway bridges, however, recurring and elaborate corrosion protection measures are necessary to maintain their structural integrity over many decades. These measures are costly, but a bridge replacement necessitated solely by neglected corrosion protection is certainly more expensive.

Image sources: Cover image | © SGappa – stock.adobe.com Rusting railway tracks | © Mbdortmund – de.wikipedia.org Comparison of steel screws | © d-jukic – stock.adobe.com Tin in its modification | © Alchemist-hp – de.wikipedia.org Corroded girder of a riveted steel bridge | © Markus Schweiss – stock.adobe.com Sacrificial anode on a ship's hull | © Zwergelstern – de.wikipedia.org

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine