How a Pipette Works

In every laboratory, small liquid volumes frequently need to be measured and dispensed with care. For this purpose, pipettes are used. However, there are a few things to bear in mind when pipetting. In this article we explain how different types of pipettes work and how to pipette correctly.

Dispensing Devices as Part of Modern Laboratory Equipment – What Is a Pipette

Today, pipettes are regarded as indispensable items of laboratory equipment. In day-to-day laboratory routines, however, the proper use of these dispensing devices often does not receive the attention it deserves. Especially when working with small volumes in the millilitre range and, even more so, in the microlitre range, correct handling of pipettes is essential, because measurement errors add up and can ultimately lead to incorrect results. For this reason, particular emphasis is placed on correct pipetting in testing laboratories and during interlaboratory comparisons, as well as on the use of properly functioning pipettes and other dispensing devices.

Different Types of Pipettes for Different Applications

Pipettes are tech nical devices for transferring and dispensing small liquid volumes in the laboratory.

nical devices for transferring and dispensing small liquid volumes in the laboratory.

Their basic mode of operation relies on drawing a liquid from any laboratory vessel into the pipette, for example from a sample container, a centrifuge tube or a volumetric flask, and then emptying it into another laboratory vessel of any kind. Implementing this very simple principle for liquid transfer and dosing has led to a wide range of designs tailored to particular applications.

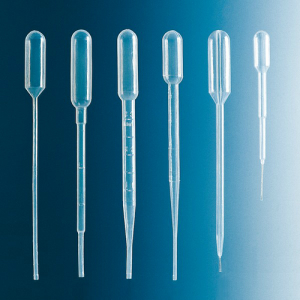

Transfer Pipettes for Moving Small Liquid Volumes

For transferring small liquid volumes where the exact volume is not critical – for example from one laboratory vessel to another – Pasteur pipettes are suitable. These are glass tubes with a drawn-out tip and a rubber bulb on top, which serves as a simple pipetting aid to generate the pressure change required to aspirate and dispense the liquid dropwise. Today, however, Pasteur pipettes are hardly used anymore.

Graduated dropping pipettes made of unbreakable plastics with an integrated bulb or bellows bulb as a non-removable pipetting aid are easier to handle. Their mode of operation corresponds to that of Pasteur pipettes. The scale that is usually present also allows a rough estimate of the volume to be dispensed.

They are most commonly used as disposable dropping pipettes made of acid and solvent resistant polypropylene (PP) or polyethylene (LDPE) for liquid volumes up to 5 ml.

Exact Volumes Require Precise Laboratory Tools

To measure the volume of a liquid precisely, accurate dispensing devices are required. For higher millilitre volumes, classic measuring and volumetric pipettes made of glass are used.

Measuring pipettes have a linear graduation between zero and the maximum pipette volume, allowing any volume within this range to be measured. A volumetric pipette (bulb pipette), on the other hand, can only be used to measure the total volume of the respective pipette. However, its measurement accuracy is higher than that of measuring pipettes, and they are usually calibrated.

Measuring and volumetric pipettes are used for volumes up to 100 ml. The previously common practice of aspirating liquids by mouth is now strictly prohibited for occupational safety reasons. Today, mechanical pipetting aids made of plastic are used instead. Pipetting bulbs in various designs, such as Peleus bulbs, Howorka bulbs, aspirators (pipetting devices) made of autoclavable natural rubber (NR) and rubber bulbs for dropping pipettes, are still common pipetting aids in the laboratory.

Measuring and volumetric pipettes are used for volumes up to 100 ml. The previously common practice of aspirating liquids by mouth is now strictly prohibited for occupational safety reasons. Today, mechanical pipetting aids made of plastic are used instead. Pipetting bulbs in various designs, such as Peleus bulbs, Howorka bulbs, aspirators (pipetting devices) made of autoclavable natural rubber (NR) and rubber bulbs for dropping pipettes, are still common pipetting aids in the laboratory.

Pipetting Very Small Liquid Volumes

Analytical chemistry and molecular biology work often require precise dosing of very small liquid volumes of less than one millilitre. Millilitre and microlitre pipettes have become standard tools for this purpose.

The original name “Marburg pipette” is a reference to its inventor, the physician Heinrich Schnitger (1925 – 1964), who developed it at the University of Marburg in the late 1950s.

The original name “Marburg pipette” is a reference to its inventor, the physician Heinrich Schnitger (1925 – 1964), who developed it at the University of Marburg in the late 1950s.

The first pipettes based on Schnitger’s piston stroke principle for reproducibly measuring small and very small liquid volumes were soon brought to market by the company Eppendorf in Hamburg. Since then, many other providers have added application-oriented models, including multichannel pipettes for simultaneous dispensing.

Direct Displacement or Air Cushion

Millilitre and microlitre pipettes are cylinder/piston pump systems that operate according to the direct-displacement principle or the air-cushion principle. In both cases, the piston stroke determines the pipetting volume, which can be preselected within a specified range in most of today’s common pipettes.

Direct-Displacement Principle

With millilitre and microlitre pipettes operating according to the direct-displacement principle, the liquid to be dispensed is drawn directly into the pipette by the piston stroke. The liquid thus comes into direct contact with the piston and cylinder. Such microlitre pipettes are structurally similar to dosing syringes used for gas and liquid chromatography (GC and HPLC) and are particularly suitable for handling non-aqueous and viscous liquids, such as glycerol, as well as liquids with high vapour pressure, such as ether or acetone.

Air-Cushion Principle

Air-cushion pipettes are the more commonly used dispensing pipettes for the millilitre and microlitre range. In this case, the liquid to be dispensed is not drawn into the pipette itself by the piston/cylinder pump system but into a disposable plastic pipette tip attached to it, from which it is then dispensed again.

Since an air cushion is located between the piston and the liquid to be pipetted in this design, the medium comes into contact only with the pipette tip. External factors such as temperature, vapour pressure or density of the liquid to be pipetted can influence the air cushion and thus also the pipetting volume. For certain applications, especially repetitive dosing, it may therefore be necessary to adjust the pipette individually.

The disposable pipette tips that are attached to the pipette are indispensable accessories for air-cushion pipettes. When used correctly, they practically rule out contamination and soiling inside the pipette body. Air-cushion pipettes are therefore preferred for dispensing sensitive media such as toxic, radioactive or bioactive solutions.

Tips for Pipetting Small Volumes Correctly

Dispensing in the microlitre range is particularly demanding because of the very small volumes involved. To achieve reliable results, the following points should be observed:

Check the Condition of the Pipette

Before using a pipette in the laboratory, you should always check its technical condition. Worn sealing rings, contamination or damage can lead to inaccurate pipetting and thus falsify results. Regular checking of pipetting accuracy and regular calibration prevent measurement inaccuracies and unacceptable deviations from the specified nominal volume.

Set the Volume Correctly

Set the Volume Correctly

A trivial but repeatedly occurring source of error is an incorrectly set pipetting volume. Therefore, you should make sure that the volume is set correctly.

The pipette tips should also be firmly attached to avoid leaks that would result in volumes deviating from the target value.

Choose the Correct Immersion Depth

An incorrect immersion depth of the pipette tip in the liquid to be dispensed can also contribute to erroneous measurement results, because there is a risk that the outside of the pipette tip will be wetted and unknown additional liquid volumes will be carried along. At small volumes, the capillary effect can also become relevant.

In both cases, the target values will be missed. If the tip is not immersed deeply enough, air may be aspirated as well. This will also distort the result. As a rule of thumb, for sample volumes up to 1 µl an immersion depth of one millimetre is appropriate. For volumes between 1 µl and 1000 µl, the immersion depth should be between two and four millimetres, while at even higher volumes up to 10 000 µl the immersion depth may be up to 6 mm.

In both cases, the target values will be missed. If the tip is not immersed deeply enough, air may be aspirated as well. This will also distort the result. As a rule of thumb, for sample volumes up to 1 µl an immersion depth of one millimetre is appropriate. For volumes between 1 µl and 1000 µl, the immersion depth should be between two and four millimetres, while at even higher volumes up to 10 000 µl the immersion depth may be up to 6 mm.

Correct Pipette Handling Matters

To pipette accurately, the user must hold the dispensing device properly in the hand and observe the pipetting angle when aspirating and dispensing the liquid. When aspirating samples, it is important to keep the dispensing pipette as vertical as possible. When dispensing the liquid, it should be held at a slight angle, ideally at a constant angle between 20° and 45°.

Correct Pipetting with a Microlitre Pipette Requires Practice

Modern microlitre pipettes usually have two clearly perceptible pressure points when pressing the pipette’s push-button, marking the respective piston positions and therefore defining the pipetting volume. This provides options for adapting pipetting to the different fluidities of the liquids to be dispensed.

In the starting position, the piston is located at the top of the cylinder, held there by spring force, in position 0. Applying finger pressure, which has to overcome the restoring force of the spring, moves the piston into the cylinder. At the first pressure point, it reaches position 1, and at the second, lower pressure point, it reaches position 2. In position 2, the pipette tip is filled to half the nominal volume when finger pressure is released to position 1, and to the full nominal volume when released to position 0. Emptying takes place in the reverse order.

In practice, especially for dispensing aqueous solutions, the empty pipette with the preset nominal volume is pressed only to the first pressure point, position 1, so that when the piston is returned to position 0 the pipette tip is only half filled. In the second step, pressing down to the lower pressure point, position 2, effectively blows out the tip to ensure complete emptying. This pipetting routine is known as forward pipetting.

When dispensing liquids with high viscosity or high vapour pressure, reverse pipetting is the method of choice. With viscous liquids in particular, there is a risk that, at the first pressure point, position 1, the preset liquid volume will not be completely taken up by the pipette tip. For this reason, in the first step the piston is pressed down to the lower pressure point, position 2, and then, by releasing it back to position 0, the pipette tip is filled. This ensures that a sufficient volume of liquid is aspirated. In the second step, the push-button is pressed only to the first pressure point, position 1, and the liquid discharged in this step is discarded. In the final step, pressing down to position 2, the lower pressure point, dispenses the correct volume.

Practice and a good feel are essential prerequisites for correct pipetting. User-related sources of error can be avoided with electronically controlled pipettes. Despite their higher acquisition costs, they are not only an attractive alternative to manually operated millilitre and microlitre pipettes, but they also help to relieve laboratory staff during routine work.

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine

Reichelt Chemietechnik Magazine